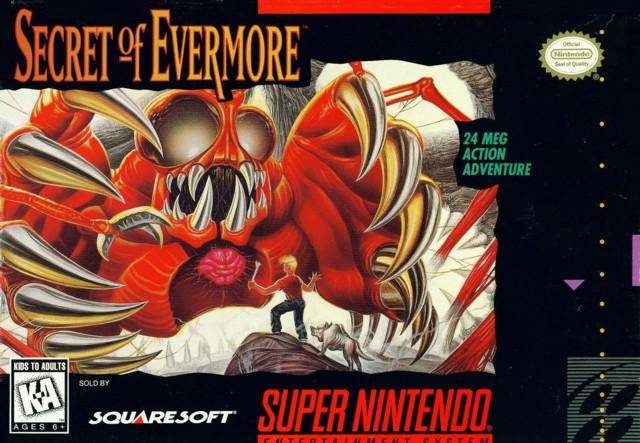

When I was younger, I had a thing for giving games a chance when they weren’t rated so well or they weren’t getting a lot of media attention. If I was at a local video store and I hadn’t seen a game before, I’d always get excited as though I was the first person in the entire world to play it and I’d found some kind of hidden gem. Back when I first started renting SNES and Genesis games on my own – before that, I needed parental or brotherly approval – the Internet wasn’t nearly as relevant as it is now and very little of it was dedicated to gaming and gaming press so having what you would call a gaming blog, back then, was kind of a brand new thing. My thing, back then, was just talking about games that I liked and trying to grow a community that knew no borders. It’s a weird thing, back then, really quite a bit more niche than it is now. When I wrote about Secret of Evermore, then, I remember saying that I got it because of its similarities to Secret of Mana, a game that stood as a beautiful and rich departure from the likes of Final Fantasy, Dragon Warrior, and Breath of Fire titles that were all the rage at the time. Delving into it now, I feel that I was able to appreciate it a little more than I did when I first tried it. Follow the jump to learn more about the game and my experiences with it!

The Game Itself

This game stands as something quite straightforward: it takes the Secret of Mana framework and drops in a fairly quirky and thoroughly American plot about a boy, his dog, an imaginary computer world and a villainous robot. Everything about this game screams out to be the equivalent of Secret of Mana, stateside, at the time: using a lesser-known American composer Jeremy Soule – way before his work on the Elder Scrolls franchise, the Harry Potter franchise, and a score of other game and movie titles – and a deviant-to-the-genre at the time art direction and storyline that fit in more with the likes of Earthbound or Lunar than that of Final Fantasy.

Instead of magic being the primary elemental power you wielded, you honed the power of alchemy, the mixing of chemicals you scavenged from the environment. Instead of your classic fantasy weaponry you bought and used weapons and armor that were indicative of the environment you were in. Instead of your typical save-the-world tropes found within the story that was sprinkled with a love interest subplot, you had a boy and his dog just trying to get back home and back to the real world. Everything in this game stood out as an example of some great stateside RPG tropes and, as a result, never really hit a mainstream stride. It would seem that this game stood more as a test of the market for this style of role playing game, almost like Squaresoft intended to create an all-American studio to produce games aimed at the market here instead of constantly localizing their Japanese titles. It was a risky venture and it was one that didn’t seem to get up off the ground. Some would say that this was a good thing but if Secret of Evermore was only one of their first ventures in this, I would say that I feel slightly upset that this never really got the chance to blossom but, as time would tell, in the future, for Squaresoft and, later, Square-Enix, Americans aren’t, in a large number, a huge supporter of the company’s approaches.

Playing the Game Then

I have to admit that I never really did get far with the game, initially. Considering that most of my gameplay time, back then, was logged with titles rented on borrowed money, my patience with a game that I didn’t know much about was a lot less than it is now. I was able to appreciate its niche approach and its subtle hints at Secret of Mana but that first boss battle was killer. It had taken me numerous attempts to try and figure out how to play the game and considering the internet wasn’t exactly as thorough as it used to be with guides and the game never seemed to come with an instruction manual, I was really strapped for a way to get past it for some time as simply grinding your way through the first lap of the game was not nearly enough to get past.

It wasn’t until I had been knee deep in emulation and doing so on my PlayStation Portable did I come back to the game and completed it for the first time on a road trip. It was then that I was truly able to appreciate the game fully but it was more of an idle way to kill time than something I really focused on. I was more focused on completing the game than really savoring it and, since then, the game has really been more of a nostalgic memory than something I ever really got to sit back and appreciate.

Even after playing the game through, now, at a leisurely pace, I remember the game feeling a lot more frustrating and drawn out than it actually was. It’s certainly a reminder of the kind of gamer I was back in the early 90s and I almost half wish I could find the write-up I did on the game back on either my Geocities page or my Angelfire page – I had both but I’m pretty sure they were both purged a long, long time ago.

Playing the Game Now

I have to say that on my playthrough, now, I’ve come to learn some of the game’s more nuanced features and approaches. I started the game up and I knew right away what I was getting into and having that experience with the game in days past really gave me a leg up on this game, not to mention experiencing the value of touching and exploring everything. I think in playing games that are similar and are probably worse for some of the things that used to irritate me about this game such as Baldur’s Gate or Fallout I grew to appreciate some of those things. This game still holds a special place in my heart but now I think it’s for a different reason.

Do any of you remember Final Fantasy Mystic Quest? Of course, you should, if you don’t. It’s universally chided as one of the worst games in the franchise and stands as a great example of what not to do with your audience. You know how I mentioned that, before, Secret of Evermore felt like an experiment of sorts to see if opening a studio stateside would have been a profitable venture? Turns out that that feeling wasn’t totally off the mark as Mystic Quest actually was a confirmed effort to do exactly what I mentioned and Mystic Quest wasn’t the only effort to do so. There were titles on the SNES and Game Boy that showed this and I still think it’s a special kind of shame that this wasn’t more appreciated by the American audience.

Looking back on this game, now, with a new set of eyes, I would say that there’s a good reason it didn’t catch with audiences here: it was a little unforgiving and it was a little too American, at the time, when games were either clearly American or Japanese and not a melding of both; gamers were just not ready for the kind of approach this game brought to the mainstream market. Unlike Mystic Quest, though, you don’t have to wade through some pretty tedious or awful gameplay in order to find the diamond in the rough: this game was, as a whole, much like Quintet games like Illusion of Gaia or Terranigma, was a diamond in the rough and should be appreciated for the great game that it is.