I recently wrote an article on my favorite virtual reality games. I think that ensuring people experience the best virtual reality games is extremely important to the health of the medium– a bad VR game is all it takes to make someone lose interest in VR and maybe lose their lunch, too.

Unfortunately, it is not always easy to identify the component of a VR experience that sends you in a rush to the nearest trash bin. I wanted to share my knowledge of core issues for both gamers and developers to keep an eye out for when playing and working in VR.

Frame Rate

Bad frame rate on computer games is noticed quite easily when it drops below 45fps. However, due to lagging frames when you turn your head, a framerate of 90fps is recommended for VR. While you can’t really tell the increased framerate when you are still and watching objects, it becomes apparent when you turn your head to look around a scene in VR. Unfortunately, with 60fps having been the standard for so long, rendering not one, but two screens at 90fps is quite the challenge for developers. This is why you’ll find that most VR games trend towards simple graphics.

User Interface

User interfaces (UI) have to be completely rethought to work well in virtual reality. While the standard for most games are active UI elements around the edge of the screen and locked position menus, neither of these work well in VR. Your peripheral vision is very sensitive to change, but is unable to focus on elements. Thus, a health bar to the side of the game would be distracting when it changed and impossible to see in detail. Locked menus in the center of the screen suddenly feel far too much like someone enthusiastically shoving a paper in your face. Certainly, you can read it, but it would be much more pleasant if they handed it to you and let you hold it at the distance that’s best for you.

The best solutions I have seen in VR for UI are systems that use the world space to host the interfaces. A particular favorite of mine are the menus and displays in Elite Dangerous. The displays are prominent on and in front of the cockpit’s windshield, far enough from your face to not be obstructive, but close enough to see clearly. The menu system is what blew me away, though. You simply turned to look to either side of the main console and a holographic menu would pop up in your spaceship in that location and become interactable with the controls. It really felt like I was using the control systems of a future space craft.

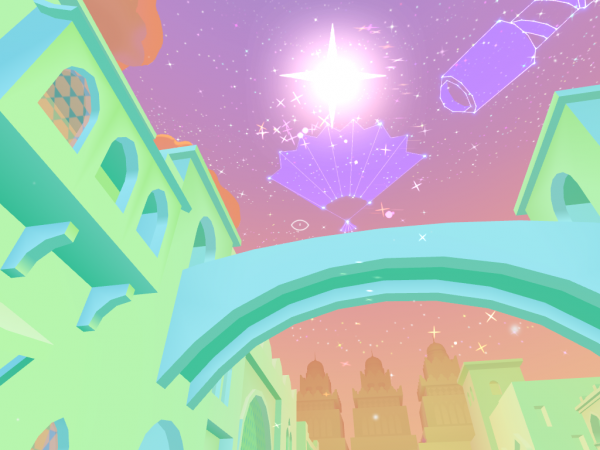

Another cool example of an ingenious virtual reality UI system is in Bazaar, where the sky acts as your inventory and your items save as constellations. The sky above you is so often unused in games, so it is great to see that space being put to use in VR and, especially, in such a creative way.

Motion

Motion within a virtual world is the fastest way to send someone reeling. When our eyes witness movement and our inner ear doesn’t feel it, a gut-churning feeling is generally produced. Of course, staying stuck in one place would greatly limit virtual reality! Luckily, there are some solutions and ways of mitigating the sickness, but, much like car-sickness, not everyone will fine VR movement pleasant.

Unsurprisingly, the best way to do VR movement is to simply let the person move themselves around the VR environment. The SteamVR experience was very transformative for many VR enthusiasts, as it allows you to walk around a space instead of being stuck in a chair or a single location. Allowing a person full control of their movement as they naturally would eliminates the motion sickness, as their body experiences the same movement. Of course, your movement is still limited by the space (currently 10’x10’) of SteamVR.

Using natural movement, but trying for an unlimited space, Omnideck 6 by Omnifinity is a 360° treadmill. In theory, it sounds like the perfect solution, a way for people to move endlessly in all directions in VR. Omnifinity has yet to develop a way for the treadmill to stop movement exactly with the user, though, so all of the demonstration videos show the player stopping and then comically being moved back by the treadmills for another second. Amusingly, this creates the exact opposite issue than what normal VR faces, as movement in real life when there is none in game can be just as unsettling.

The Virtuix Omni, a concave platform that you walk and run on using a harness and special shoes, is certainly cheaper than the Omnideck. It allows you to stop instantly, but requires “sliding” steps to move and stops you from being able to squat, lean and engage in other similar movements. A good solution for some games, but it still is yet another expensive piece of hardware that customers have to purchase.

So what are non-hardware approaches to movement in virtual reality?

Placing the player in a moving object and keeping the player stationary within the object is one of the best solutions. Games like Vox Machinae and Eve: Valkyrie place you in command of a mech or space ship, allowing you to feel perfectly snug in your chair while controlling the movement of your craft. For most people, having stationary elements around them is all that is needed to solve the movement problems in VR.

Again, this is a solution, but not to all VR problems. With our current technology, sometimes you’ll want to sit in a chair and explore the world in a first person virtual view. There are a few easy ways to make this as painless as possible. First, the movement speed should be kept fairly low. Oculus recommends 1.4m/s for a walk and 3m/s for a jog. Movement above this speed starts to make one feel pretty nauseous. Second, acceleration is much more disorienting than constant velocities. It is much better to have movement that goes from 0 to speed rather than have a noticeable acceleration at the start. This is particularly important for turning. Finally, it can be very disorienting for “forward” to not be the direction you are looking. We humans rarely strafe in real life! The second-most vomit-inducing VR experience I’ve ever had was catapulting through the air and trying to look where my next jump should be. The combination of moving quickly and moving in a direction I wasn’t looking at was very rough. While it might be hard to have good movement controls that only allow you to move in the direction you are looking – a big part of VR is being able to look around naturally, after all – it is smart to avoid gameplay that requires looking in one direction while moving in another, especially when the player does not have full control of that movement.

Convergence Artifacts

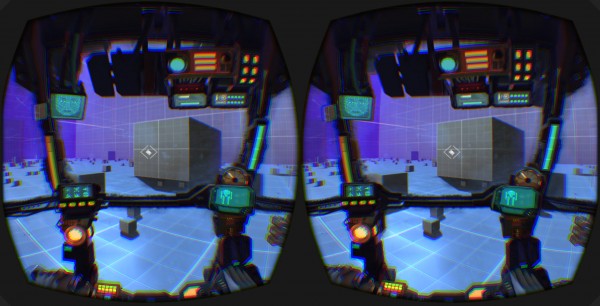

What is a convergence artifact? Basically, it’s what you see when your eyes receive incompatible information about an object. It often looks like a flickering and can be vary strenuous as your eyes fight for dominance and focus to determine the artifact’s visual form. The most obvious form of this that I’ve encountered was a game in which the end screen was rendered in one eye and not the other. It caused immediate tension in my eyes and I was more than happy to quickly remove the VR headset. While the developer informed me that he had just added it to the game and the one-eye rendering was temporary, I offered the advice to avoid such temporary menus in the future, they definitely do more harm than good.

Hopefully, most games will avoid that obvious creation of eye strain. Many VR games, especially ones created first for monitors, will likely face another difficulty that causes these convergence artifacts. Specular mapping and shaders are calculated from the angle that they are viewed at. However, with two cameras, one for each eye, the calculated results don’t always work well together. This may cause grass to render in two different ways, seemingly flickering for the user, or for some objects just to look inexplicably off. It seems that the best approach is to calculate shaders and specular mapping from a single view parameter for both eyes.

Unfortunately, it is not always a simple problem to solve and can be even harder to detect. So if your eyes feel inexplicably strained after playing a VR game for a while, give the details a close look to make sure the strain isn’t being caused by these artifacts.

Camera

Not all VR games are first person and a third person camera view can be awesome. In AirMechVR, you view the RTS battlefield from the normal god-like position, but you have it laid out on a table in front of you, like you were playing a tabletop game. The experience is enhanced more when you realize the room you are playing in is actually your main base that you’re trying to protect, which gives a cool dual first/third person perspective of the battle. You can fly what seems to be a little toy AirMech over a toy base, then look up and see the craft in full size above you.

The most important aspect of camera use in VR, though, is that the control of the camera always belongs to the player. Many non-VR games take the camera away from the player to pan across a new landscape or to set up a better view angle for a dialog scene. These camera motions done in VR bring about the same nausea that poor movement causes for similar reasons, simply because camera movement in VR is interpreted as motion by your brain.

The most vomit-inducing VR experience I’ve had was when I died in one of the games that I was playing. Instead of fading to a death screen or freezing the camera and game, my character rag-dolled to the ground, causing the VR view to flip and fall. It was the equivalent of your vision going on a tumble that your body didn’t come along for and my stomach found it most-upsetting.

Hopefully, with these points in mind, you can recognize troublesome VR experiences, whether it is to find a good VR game, identify why a game is making you sick or to improve a game of your own!